Latest Research

St Bees Man – the ongoing research story this century

After the discovery of what became known as St Bees Man, John Todd and his wife Mary spent much time trying to answer the question asked by the mortuary attendant back in 1981 – “Name of deceased?”

John’s researches pointed him in the direction of Anthony de Lucy but one of the main unanswered questions was the identity of the female skeleton lying beside the lead-shrouded body in the vault.

Maud de lucy – further evidence

The lady, originally thought to be in her thirties, had been buried in an extension of the original vault and had therefore died after the man. Anthony’s wife survived him, remarried and died in London in her seventies, and Anthony’s sister Maud was the wrong age, so the lady remained a mystery.

In the 2000’s Chris Knusel, working from the University of Exeter, took up the research and applied the latest scientific techniques to the bones of the lady. Using isotopic analysis, he discovered much about her diet and where she might have been brought up, but in particular he pointed up the fact that she had a permanently dislocated jaw and it was probable that she was much older than at first had been thought, perhaps in her fifties. He also noted the significance of a fragment of heraldry that was built into the wall of the bell-ringing chamber of the priory which gave further indication that the lady could well be Maud.

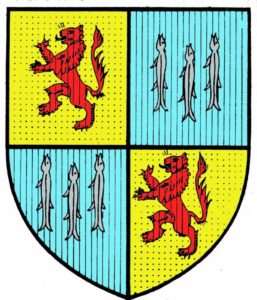

Maud inherited the de Lucy estates when her brother died and later married Henry Percy, linking the de Lucy estates with the Percy land centred around Alnwick castle in Northumberland. Maud insisted, as part of the marriage settlement, that the de Lucy heraldry (three pikes) would, from that time, be quartered with the Percy Lion. The fragment in the bell-tower shows exactly that and it was thought that this fragment might well have been on the side of the vault containing the remains of Maud and her brother.

Maud died in 1398 aged about 55, perhaps coming back to St Bees in death to be reunited with her brother and where her niece, Anthony’s daughter, was buried aged about 2 or 3. The fragment of heraldry, placed in the Priory by chance, becomes an important piece of the historical jigsaw, it is not quite Maud’s signature but quite close to it.

.

The Percy Arms quartered with the Lucy arms; created for Maud de Lucy. This the fragment in the belfry at the Priory.

Maud’s Arms

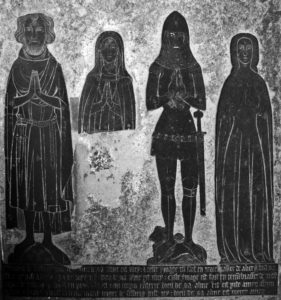

Brass commemorating Roger de Felbrig in Fell brigg church, Norfolk.

The Northern Crusade in Prussia and Lithuania

Since then, much has been discovered about the ill-fated last journey of Anthony de Lucy to Prussia. In 1367 having inherited the estates from his father who died two years before, he decided to join a number of knights who were going to Prussia to join the Teutonic Knights in the long-running Northern Crusade against the heathen Slavs. In the fourteenth century this was not uncommon, although it may seem strange to us that Anthony would leave his wife and young daughter on such a dangerous mission at this time.

Christian knights went on the Northern Crusade for a variety of different reasons. There was spiritual preferment whereby that it was taught that a crusader dying in battle did not have to wait in purgatory before heaven. There was family and individual prestige to be gained and it was relatively easy to go for a few months for the winter or summer fighting season when there was a lull in the war with France. The Crusade had become so organised and popular that something like a “package tour” could be arranged.

Anthony de Lucy had estates in Lincolnshire around Holbeach, and it was from that area that a sizeable group of knights made plans to leave in the autumn of 1367. Among them was Roger Felbrigg, John de Multon and Anthony de Lucy. In his paper John Todd states that both the last two borrowed money from Elizabeth Perrers and it was assumed that they travelled together. A recent letter has been uncovered which confirms that assumption. It was written by John de Multon to his wife and is dated 23rd November 1367. He writes; “Dear wife know that Anthony de Lucy and I and all our company make our way towards the parts of Spruz (Prussia) the day of the making of these letters…..” It is sad that this letter appeared after John Todd’s untimely death as it confirms his theory.

So that company crossed the channel and made the several weeks journey to what is now Lithuania to join the numbers of knights from other places and countries assembled at Marienburg Castle, which was the headquarters of the Teutonic Knights. It was probably too late for any action that year, which stopped in very cold weather and never went over Christmas, so the English party would have been able to enjoy Marienburg; which was the equivalent of a five star resort. The Teutonic Knights had a reputation for honouring foreign knights with fine banquets and entertainments until the summer “reyse” or fighting season started in August when the ground was dry. And so they waited.

There is some evidence that the English party was used to attack a fort that had been built at Kaunas and it is reported that “three of our men were killed from the walls”. The injuries of Anthony de Lucy, a fractured jaw and punctured lung fit, with this. The three killed seem to be Anthony, John de Multon and Roger Felbrigg with the most probable date being 16th September 1368.

It would be expected that foreign knights who died in Prussia would be buried in the church in Konigsburg. On a memorial brass commemorating Roger Felbrigg in his home church it states that “he died in Prussia and there his corpse is buried”. It is probable that John de Multon would have been buried there as well, although there is no information about it.

It appears that two extraordinary things happened with Anthony. Firstly it seems he was wrapped in his shroud and transported back to St Bees as a complete body; there is no record of anybody else being treated in the same way from Prussia. Secondly, and perhaps even more strangely, the decomposition of the body seems to have stopped after a short time with the formation of a material called adipocere acting as a natural preservative.

Adipocere in dead bodies forms under a variety of different environments, favourable factors are anaerobic conditions and the presence of a lot of body fat, but it is normally a slow process taking weeks or months, usually to preserve a small part of a body. In this extraordinary case the adipocere seems to have formed rapidly and almost throughout the body. In the post-mortem it was possible to see the structure of the heart, to look at the state of the liver and kidney and to use a syringe to suck liquid blood out of the lungs. It was even possible to have a guess at what had been eaten for breakfast, namely porage and grapes. If the body was Anthony de Lucy, then what could be seen on the operating table was over 600 years old. The only part of him that had totally decayed was his brain.

Kaunas Castle, Lithuania. (Under GNU licence. Author: Marcin Szala from Wikimedia Commons)

Marienburg Castle, Poland (Under GNU licence.Author; “Dehexer” from Wikimedia

Questions still unanswered

Although more pieces have been put in the jigsaw, and nothing contradicts existing theories, many questions remain:

* Anthony’s return journey was probably by boat to an East England port, but that is guesswork.

* There is no forensic evidence from the lead, linen or string to link the burial site in St Bees with Prussia.

* The hair held round Anthony’s neck is a mystery, but Sandy Grant from Lancaster University suggests it is most likely his wife’s as he died in what was a war zone, so the hair might possibly have been taken with him as a love token.

Further reading

More information on this unique story can be found in the following.

- “The Northern Crusades” by Eric Christiansen, Penguin books, 1998.

- “Chivalry Kingship and Crusade” by Timothy Guard

- “The St Bees Lord and Lady and their Lineage” by Alexander Grant.

- “The identity of the St Bees Lady” by C.J.Knusel et al (published in Medieval Archaeology 2010)

- Article on the Teutonic Knights on Wikipedia

Guided tours and talks

Please note we are happy to talk about St Bees Man to interested groups. Please make contact via the webmaster of this site for further enquiries.

Text by Chris Robson, St Bees Village History group Feb 2014