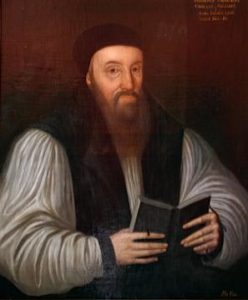

Archbishop Edmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal of St. Bees

1517-1583

Archbishop of York (1570 – 1575)

Archbishop of Canterbury (1575 – 1583)

Remarkably, the small West Cumbrian village of St. Bees produced two of the Archbishops of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I; Archbishop Edmund Grindal of Canterbury and Archbishop Edwin Sandys of York. This article describes the life of Grindal and the founding of St. Bees School.

Birthplace and Early Life

Edmund Grindal was born about 1517 at Cross Hill House, St. Bees. His father, William Grindal, was a tenant farmer of St. Bees Priory, and occupied one of the few large stone buildings in the village. It is only recently that evidence has come to light which has settled the centuries of speculation over his actual birthplace.(1) (see Birthplace). Little is known of his early years, but his childhood companion was Edwin Sandys, who was later to follow in Grindal’s footsteps as Bishop of London and Archbishop of York. Certainly it is remarkable that two St. Bees boys went on to such high office in such turbulent times, and suggests an unusually good early education.

Two stories remain from his childhood. One, that he was saved from a stray arrow piercing his heart by a thick book under his cloak, another, that he saved his father from drowning by pulling him back over a bridge which soon after collapsed into a raging torrent.

Rise in the Reformed Church

Grindal proceeded to Magdalene and Christ’s Colleges and then Pembroke Hall, Cambridge, where he graduated BA and was elected fellow in 1538. Having obtained his MA in 1541, he was ordained deacon in 1544 and was made Proctor and Lady Margaret Preacher in 1548-9. Probably through the influence of Nicholas Ridley, who was Master of Pembroke Hall, Grindal was selected as one of the Protestant disputants during the Royal Visitation of 1549, when he disputed the dogma of “transubstantiation” (the belief in the actual conversion of communion bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood).

When Ridley became Bishop of London, he made Grindal one of his chaplains and gave him the precentorship of St Paul’s Cathedral. Grindal was soon promoted to be one of King Edward VI’s chaplains and prebendary of Westminster, and in Oct 1552 was one of six Protestant authorities to whom the Forty-two Articles of Religion, compiled by Archbishop Cranmer, were submitted for examination before being sanctioned by the Privy Council. He caught the eye of William Cecil, later Lord Burghley, Lord Treasurer and trusted adviser to Elizabeth I, partly through his contribution to the debates on the communion; a topic of great interest to the reformed Church. But, according to John Knox, Grindal distinguished himself from most of the court preachers in 1553 by denouncing the worldliness of courtiers and foretelling the evils that would follow the King’s death.

Exile and Return

On the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary in 1553, these evils did happen to many of the courtiers, over 200 Protestants who refused to recant being put to death as Mary tried to turn the Country back to the Catholic faith. As a rising star of the Protestant Church, Grindal was obliged to flee England, and made his way to exile in Strasbourg. From there he travelled the continent, meeting other exiled Protestants. At Frankfurt, he tried to settle the disputes between the “Coxians”, who regarded the 1552 Book of Common Prayer as completely reformed, and the “Knoxians”, who wanted greater simplification. This failed, and theses two parties in the English Church in exile remained split.

Probably the only weapon of the exiles against the Catholic Queen Mary was the publication of books and tracts. Grindal helped John Foxe in the production of his famous “Book of Martyrs”. Grindal recorded the testimonies of those suffering under Mary’s reign of terror. These were passed to John Foxe and included in his “Acts and Monuments”. But when Queen Mary died in 1558, he tried to discourage Foxe from printing, until more accurate information could be obtained on their return to England. However, Foxe disregarded this and had it published from Basle in 1559. Foxe is the name that is remembered today; not Grindal. Despite this there continued a long association between the two.

Grindal returned to England in January 1559, to find an ardently Protestant Queen Elizabeth I on the throne, and himself in a position of some considerable reputation and respect. He was appointed to the committee to revise the liturgy, became a court preacher again, and was one of the Protestant representatives at the staged disputation with the Papists in Westminster Abbey, which led to the religious strategy of Elizabeth’s second session of Parliament. Later in the year he was elected Master of Pembroke Hall, and was made Bishop of London in succession to Edmund Bonner. He had become one of the pillars of the Established Church. –

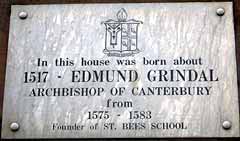

Plaque on wall of Grindal House

Grindal House in St Bees

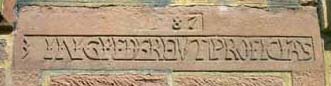

The original St. Bees School block of 1587-88

The lintel stone of the entrance to the original school block. 1587 “Enter, so that you may make progress”.

Grindal’s job was to support the work of Archbishop Parker in enforcing the uniformity of worship in the English Church. This meant steering a middle course between Puritans and Roman Catholics who did not conform to the Act of Uniformity. Grindal had worries about vestments and other traces of “popery”, but on the other hand, was reluctant to execute judgments on English Puritans. As it was, even Grindal’s attempts merely to enforce the use of the surplice caused angry protests in the difficult Diocese of London.

In 1570 Grindal was appointed Archbishop of York, an Archdiocese where there were few Puritans and enforcing uniformity would be mainly concerned with Roman Catholics. On arriving he comments that he was not well received, and that the gentry were not “well-affected to godly religion and among the common people many superstitious practices remained”. At this time his health gave him great trouble, and it was many months before he could appear in the great Minster at York, to occupy his Archdiocesan seat. Despite this stay in the North, he was not able to visit his native St. Bees.

Primate and Prisoner

In January 1576, following the death of Archbishop Parker, Grindal was made Archbishop of Canterbury; partly it is thought through the influence of William Cecil, who advised Elizabeth to have someone who had the support of the Puritan reformers. However, the experiment was short-lived.

Very soon, Elizabeth requested Grindal to suppress the “prophesyings”, or public debates of the clergy at which portions of Scripture were discussed openly. These had come into fashion among the Puritan clergy, and could be used to propagate non-conformity and discontent with the Established Church. Elizabeth even wanted him to discourage preaching. Grindal objected strongly, to no avail, and in June 1577 he was suspended from his legal jurisdiction and was effectively put under “house arrest” in his palace at Croydon. He was still, however, the Spiritual Head of the Church.

He stood his ground, and in 1578 the Queen wished to have the Archbishop deprived of his post. She was dissuaded from this extreme course, but Grindal’s suspension was continued in spite of a petition from the Church Convocation in 1581 for his reinstatement. Elizabeth then suggested that he should resign; but he declined to do so, and an apology to the Queen seems to have had some effect, as he was legally reinstated towards the end of 1582. But his infirmities were worsening, particularly his increasing blindness, and he resolved to resign. While making preparations for this, he died and was buried in Croydon parish church.

Was Grindal a good moderating force at a difficult time in the English Church, or an indecisive and weak leader? This was one of the most turbulent religious times for several hundred years in England, and the swinging of the pendulum from Catholic to Protestant twice over had deeply upset the stability of the country. It was Grindal’s task to enforce the uniformity of the state protestant religion, and at the same to strive for a truly reformed church.

It was acknowledged that he did the work of enforcing uniformity against the Roman Catholics with good-will and considerable tact, but this was not strong enough for Elizabeth, though was in line with what much of the senior clergy themselves thought. The debate has rumbled on over the centuries, and the answer is probably lost in the arcane world of Elizabethan court politics.

His Legacy

The most enduring monument to Grindal has proved to be the “free grammar school” which he founded in his native village of St Bees, where he had not been for perhaps forty-five years. The school was to be built and at a cost of £366.3s.4d. and endowed with annual revenues of £50. Nicholas Copeland was nominate by Grindal as the first Headmaster.

Only three days before his death Grindal had published statutes for the school, a series of minute and specific regulations; a treasury of information for historians of Tudor education. Although the foundation was to be sometimes at risk in its early years, a school building had been erected by 1588 and a tradition of learning had begun which has continued without a break for four centuries.

Grindal linked the school with his own college of Pembroke Hall by founding two scholarships for St Bees boys as well as a fellowship. Another St Bees scholarship was founded at Magdalene College with an endowment of £100.

The largest and most significant benefaction outside St Bees was made to the Queen’s College Oxford, which had strong Cumbrian connections. A fellowship and two St Bees scholarships were endowed, and Queen’s was linked in perpetuity with the school through the provision that its provost was to serve as a governor and appoint the headmaster.

For the poor of St. Bees he left £13.6s.8d, and to St. Bees Church he gave his communion cup.

Finally, there is a botanic legacy. Grindal was a keen botanist, and introduced the Tamarisk to Britain, having first seen it in exile on the Continent. It was planted in the grounds of the Palace at Fulham, when he was Bishop of London.

TIMELINE

Monarch |

Archbishop |

Events in Grindal’s Life |

|

| 1500 |

Henry VIII |

William Warham |

|

|

Born about 1517 |

|||

| 1525 | |||

|

Thomas Cranmer |

|||

|

1538 – Graduated B.A. |

|||

|

1541 – Fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge |

|||

|

1549 – Master of Pembroke College |

|||

| 1550 |

Edward VI |

1551 – Chaplain to Edward VI |

|

|

Mary |

Cardinal Pole |

1553-1559 – Exiled on the Continent |

|

|

Elizabeth I |

Matthew Parker |

1559 – Bishop of London |

|

|

1570 – Archbishop of York |

|||

| 1575 |

Edmund Grindal |

1576 – Archbishop of Canterbury |

|

|

1577- Dispute with Elizabeth I |

|||

|

1583 – Founded St. Bees School shortly before his death |

|||

|

John Whitgift |

|||

| 1600 | |||

|

Not to scale |

Notes

1. This was established by John & Mary Todd, and published in the Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society (CWAAS) in 1999.