Village History in a nutshell

Pre-History.

Evidence of Mesolithic and Bronze Age habitation has been found in St Bees, in the form of small flint tools called microliths thrown up by ploughing or earthworks.

Roman Era.

Curiously, despite much searching, no evidence of Roman occupation can be found, although St Bees Head must have been a good vantage point for observation and signalling.

The Dark Ages.

The name St Bees is a corruption of the Norse name for the village, which is given in the earliest charter of the Priory as “Kyrkeby becok”. This can be translated as the “Church town of Bega”. Bega is our local saint, said to be an Irish princess who fled across the Irish Sea to St Bees to avoid an enforced marriage to a Viking prince; sometime after 850 AD. Carved stones at the Priory show that Irish-Norse Viking influence was felt here in the 10th

The West Door of the Priory Ca 1120

The Normans.

The Normans did not reach this part of Cumbria until 1092, and William le Meschin, Lord of Egremont, used the existing religious site to found a Benedictine priory for a prior and six monks subordinate to St Mary’s Abbey at York, probably not long after 1120.

The priory had a great influence on the area. The monks worked the land, fished, and extended the priory buildings. The ecclesiastical parish of St Bees was large and stretched to many of the western valleys. The priory was closed at the dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539 by Henry VIII, but the nave and transepts of the monastic church have continued in use as the parish church until the present day.

St Bees School.

Remarkably, St Bees produced two of the archbishops of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I; Edmund Grindal, Archbishop of Canterbury and Edwin Sandys, Archbishop of York. Grindal was born in Cross Hill House in about 1519. This still exists, and is marked with a plaque. He was probably educated at the Priory. A devout Protestant, he was appointed bishop of London just before Edward VI died, but was not enthroned, and had to flee to Strasbourg when the Catholic Mary I became Queen.

On Mary’s death Grindal returned, was appointed Bishop of London, then Archbishop of York, and finally Archbishop of Canterbury. His boyhood friend Sandys followed in his footsteps. Unfortunately Grindal opposed Elizabeth I by liberalising the church and was put under house arrest. He died in 1583, shortly after founding St Bees School which exists today as a co-educational independent school.

Growth of the village.

The focus of the village moved in the 1500’s to the south side of Pow beck, away from the Priory, which was dissolved in 1539, and it was here that the Main street developed.

At this time stone came into use as a domestic building material, and the oldest surviving house, Grindal’s birthplace on Cross Hill, dates from 1512. Other early houses are Stonehouse farm and it’s older barn next door. Gradually stone-built dwellings appeared along the Main street, of which Nursery Cottage is a fine example, and the present Main Street was created from a string of farms and farmworkers’ dwellings. The walking tour booklet advertised below is an excellent way of exploring how the village grew.

The 19th Century

The 19th century saw the start of great changes. In 1816 St Bees Theological College was founded and at one time had over 100 students. This was a pioneering institution; being the first Church of England clergy training college outside Oxford or Cambridge. The theological students lodged in the village. In 1846 St. Bees School started its era of expansion with the building of the quadrangle, and all this growth provided extra income to the village in providing services and lodgings.

Coming of the railway.

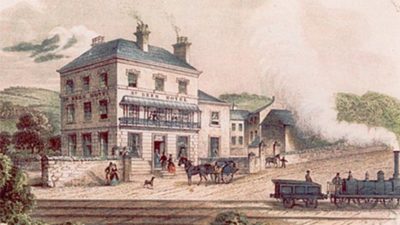

Probably the greatest changes were after 1849 when the railway reached the village. This led to the exploitation of the fine St Bees red sandstone. Huge amounts were quarried, much of it for building Barrow-in-Furness. This was transported from the quarries on Outrigg to the railway station, and the main street had to be re-graded to handle this traffic. The village quarries have been closed for nearly a century, but there are still four working sandstone quarries in West Cumbria.

The railway also attracted the professional classes commuting to Whitehaven and Workington, and this led to the building of many of the larger houses, and Lonsdale Terrace and Vale View.

The railway brought tourists for the first time, who previously had to travel by steam packet to Whitehaven or take the coach, and in 1851 we find the Lord Mayor of London holidaying at the Seacote Hotel.

Iron Industry

The boom in the West Cumberland Iron industry in the 1800’s also provided much employment, and many village men worked in the iron ore mines at Cleator and Bigrigg. Thus the 19th century saw the change from a rural economy based on agriculture, to the more diversified role of a dormitory village for professional and industrial worker alike, and its growth into an academic centre.

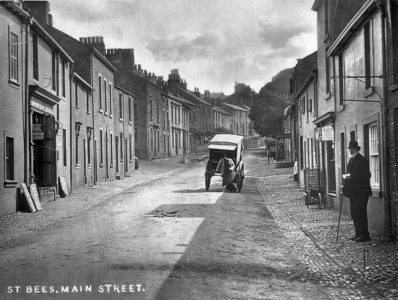

The view of the Main Street about 1900 is now of an urban street. By this time most of the farms had disappeared, and many houses had been built to house commuters or lodge theological students. The grading of the road to allow sandstone traffic can be seen behind the parked van.

The 19th Century saw the building of new houses for commuters

20th Century.

The start of the 20th century saw a further consolidation in agriculture, and this has continued to today; there are only a few farms left, and only one on the main street.

Industrial decline also hit West Cumbria as a whole, particularly after the boom years of both world wars. However, following the Second World War, two local major industries were established which had a profound effect on the community. These were Marchon Chemicals at Whitehaven, and UKAEA/BNFL at Sellafield; both used village labour released by the declining heavy iron and mining industries. They also brought in the technical and professional middle class into the village, rather like the first arrival of the managerial middle class a century earlier.

There is now an extensive science park – Westlakes, on the northern fringe of the parish, at which the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority has its national headquarters.

The village economy, like most of West Cumbria, is now mainly reliant on the Nuclear industry and it’s supply chain, But the last two decades have seen a significant revival of the tourism sector, helped by the Heritage Coast of St Bees Head, and the start of the Wainwright Walk, devised in 1973.

Walking tour of village history

This new edition of “One thousand years of Village history” is a walking tour of village history.

Re-written May 2013, and on sale in the Priory Church History area now. The history area has extensive displays of village history and you are very welcome to browse. Enter the church by the west door, and it’s on the right.